(UPDATE on 8-21-07: Some of John Davenant’s writings can be found online for free HERE).

John Davenant, “A Dissertation on the Death of Christ,” in An Exposition of the Epistle of St. Paul to the Colossians, trans. Josiah Allport, 2 vols. (London: Hamilton, Adams, and Co., 1832), 2:401–404.CHAPTER IV.

THE SECOND PROPOSITION STATED, EXPLAINED AND CONFIRMED

IN our first proposition we endeavored to shew that the death or merit of Christ was appointed by God, proposed in the holy Scriptures, and to be considered by us, as an universal remedy applicable to all men for salvation from the ordination of God. And on this account we hesitate not to assert that Christ died for all men, inasmuch as he endured death, by the merit and virtue of which all men individually who obey the Gospel may be delivered from death and obtain eternal salvation. But because some persons in such a way concede that Christ died for all men, that with the same breath they assert that he died for the elect alone, and so expound that received distinction of Divines, That he died for all sufficiently, but for the elect effectually, that they entirely extinguish the first part of the sentence; we will lay down a second proposition, which will afford an occasion of discussing that subject expressly, which we have hitherto only glanced at slightly by the way. This second proposition, therefore, shall be reduced into this form; if it is rather prolix, pardon it. The death of Christ is the universal cause of the salvation of mankind, and Christ himself is acknowledged to have died for all men sufficiently, not by reason of the mere sufficiency or of the intrinsic value, according to which the death of God is a price more than sufficient for redeeming a thousand worlds; but by reason of the Evangelical covenant confirmed with the whole human race through the merit of his death, and of the Divine ordination depending upon it, according to which, under the possible condition of faith, remission of sins and eternal life is decreed to be set before every mortal man who will believe it, on account of the merits of Christ. In handling this proposition we shall do two things. First, we shall explain some of the terms. Secondly, we shall divide our proposition into certain parts, and establish them separately by some arguments.

In the first place, therefore, is to be explained, what we mean by mere sufficiency, and what by that which is commonly admitted by Divines, That Christ died for all sufficiently. If we speak of the price of redemption, that ransom is to be acknowledged sufficient which exactly answers to the debt of the captive; or which satisfies the demand of him who has the power of liberating the captive. The equality of one thing to another, or to the demands of him who has power over the captive, constitutes what we call this mere sufficiency. This shall be illustrated by examples. Suppose my brother was detained in prison for a debt of a thousand pounds. If I have in my possession so many pounds, I can truly affirm that this money is sufficient to pay the debt of my brother, and to free him from it. But while it is not offered for him, the mere sufficiency of the thing is understood, and estimated only from the value of it, the act of offering that ransom being wanting, without which the aforesaid sufficiency effects nothing. For the same reason, if many persons should be capitally condemned for the crime of high treason, and the king himself against whom this crime was committed should agree that he would be reconciled to all for whom his son should think fit to suffer death: Now the death of the Son, according to the agreement, is appointed to be a sufficient ransom for redeeming all those for whom it should be offered. But if there should be any for whom that ransom should not be offered, as to those it has only a mere sufficiency, which is supposed from the value of the thing considered in itself, and not that which is understood from the act of offering. To these things I add, If we admit the aforesaid ransom not only to be sufficient from the equality of the one thing to the other, and from his demand, who requires nothing more from the redemption of the captives; but also to be greater and better in an indefinite degree, and to exceed all their debts, yet if there should not be added to this the intention and act of offering for certain captives, although such a ransom should be ever so copious and superabundant, considered in itself and from its intrinsic value, yet what was said of the sufficiency may be said of the superabundance, that there was a mere superabundance of the thing, but that it effected nothing as yet for the liberation of the persons aforesaid.

Now to this mere sufficiency, which regards nothing else than the equal or superabundant worth of the appointed price of redemption, I oppose another, which, for the sake of perspecuity, I shall call ordained sufficiency. This is understood when the thing which has respect to the ransom, or redemption price, is not only equivalent to, or superior in value to the thing redeemed, but also is ordained for its redemption by some wish to offer or actual offering. Thus a thousand talents laid up in the treasury of a prince are said to be a sufficient ransom to redeem ten citizens taken captive by an enemy; but if there is not an intention to offer, and an actual offering and giving these talents for those captives, or for some of them, then a mere and not an ordained sufficiency of the thing is supposed as to those person for whom it is not given. But if you add the act and intention offering them for the liberation of certain persons, then the ordained sufficiency is asserted as to them alone. Further, this ordained sufficiency of the ransom for the redemption of a captive may be twofold: Absolute; when there is such agreement between him who gives and him who receives this price of redemption for the liberation of the captives, that as soon as the price is paid, on the act of payment the captives are immediately delivered. Conditional; when the price is accepted, not that it may be paid immediately, and the captive be restored to liberty; but that he should be delivered under a condition if he should first do something or other. When we say that Christ died sufficiently for all, we do not understand the mere sufficiency of the thing with a defect of the oblation as to the greater part of mankind, but that ordained sufficiency, which has the intent and act of offering joined to it, and that for all; but with the conditional, and not the absolute ordination which we have expressed. In one word, when we affirm that Christ died for all sufficiently, we mean, That there was in the sacrifice itself a sufficiency or equivalency, yea, a superabundance of price or dignity, if it should be compared to the whole human race; that both in the offering and the accepting there was a kind of ordination, according to which the aforesaid sacrifice was offered and accepted for the redemption of all mankind. This may suffice for the explanation of the first term.

My remarks:

Davenant begins by showing that he wants to refute the strict particularist view (as over against Davenant's dualistic view) of some who, in the "same breath," say that Christ died in some sense for all men, but then hold that he died for the elect alone. They give lip service to the sufficiency/efficiency formula of the schoolmen or "Divines", but mean something different by it. Davenant addresses this issue by distinguishing between a "mere sufficiency" and an "ordained sufficiency." First, a "mere sufficiency," according to Davenant's categories, is unrelated to intention and active principles of actual giving and offering. That's crucial to note. A thousand pounds may have intrinsic worth or sufficiency to free a given prisoner, but if it is not given or offered to him, then it is "merely sufficient." Two thousand pounds may be of superabundant sufficiency, intrinsically considered, for the payment, but if it is not offered then it is merely sufficient for that prisoner. As over against this mere sufficiency, there is the sense of an ordained sufficiency. This sense of sufficiency is related to intention and offering. As Davenant says, "This is understood when the thing which has respect to the ransom, or redemption price, is not only equivalent to, or superior in value to the thing redeemed, but also is ordained for its redemption by some wish to offer or actual offering." Equivalent intrinsic worth (whether a moral or pecuniary equivalency) is joined to an intention and active giving or offering with the sense of an "ordained sufficiency."

Also, within the sense of an ordained sufficiency, he makes the twofold distinction between an "absolute" and a "conditional" agreement. With an absolute sort of agreement, "as soon as the price is paid, on the act of payment the captives are immediately delivered." An absolute payment ipso facto liberates, as Charles Hodge puts it, the recipients when the payment is made. In a conditional agreement, the captive is restored to liberty after he or she first does something. There are terms or conditions that must be met, even though the payment has already been made. Davenant would argue that the condition for being liberated or saved unto eternal life is faith. Even though Christ has made a morally equivalent "payment" in dying a death that every sinner deserves, no one is, on that basis alone, saved. Even though Davenant uses terms such as "payment," "price," "purchase" etc., he is not making Christ's death a literal pecuniary or commercial payment. He is speaking analogically or metaphorically. There is a valid comparison between the paying of a moral debt and the paying of a commercial debt (the scriptures liken these things metaphorically), but the language should not be made univocal so as to discount a measure of discontinuity in the comparison. As Dabney says regarding some analogies he makes, "None will deny that the discussion of God's nature and activities should be approached with profound reverence and diffidence. One of the clearest declarations concerning him in the Scriptures is, that we may not expect to "find out the Almighty unto perfection" [(Job 11:7)]. Should a theologian assume, then, that his rationale of God's actings furnished an exhaustive or complete explanation of them all, this alone would convict him of error. It must be admitted, also, that no analogy can be perfect between the actions of a finite and the infinite intelligence and will. But analogies may be instructive and valuable which are not perfect; if they are just in part, they may guide us in the particulars wherein there is a true correspondence. And the Scriptures, which do undertake to unfold "parts of his ways" [(Job 26:14)]], will be safe guides to those who study them with humility."

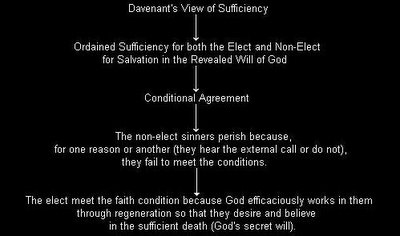

The position of John Davenant is that Christ paid a morally equivalent price for the redemption of all mankind intentionally, but the reception of the benefits unto eternal life are based in conditions; such as, "he who believes shall not perish, but he who does not believe shall perish." Belief in Christ is the necessary condition for the enjoyment of eternal life, but none will perform this condition except the elect, for God grants to them alone the moral ability to believe as a result of his eternal decree or predestination. This sets Davenant's view apart from Arminianism as well. We might illustrate Davenant's position in the following way:

No comments:

Post a Comment