51. Resolved, that I will act so, in every respect, as I think I shall wish I had done, if I should at last be damned. July 8, 1723.

55. Resolved, to endeavor to my utmost to act as I can think I should do, if I had already seen the happiness of heaven, and hell torments. July 8, 1723.

December 31, 2005

Serious Resolutions

Posted by Tony Byrne at 12/31/2005 4 comments

Labels: Jonathan Edwards

December 30, 2005

On Essential Doctrines and the Difference Between Affirmation and Denial

A square has four sides, and an object that does not have four sides is not a square. In other words, having four sides is essential to squareness. A square's color may change, but the color is a non-essential quality.

A square has four sides, and an object that does not have four sides is not a square. In other words, having four sides is essential to squareness. A square's color may change, but the color is a non-essential quality.Posted by Tony Byrne at 12/30/2005 3 comments

Labels: Essentials, Logic

December 25, 2005

Christmas Thoughts

When the Father long to show

The love He wanted us to know

He sent His only Son and so

Became a holy embryo

Chorus

That is the Mystery

More than you can see

Give up on your pondering

And fall down on your knees

A fiction as fantastic and wild

A mother made by her own child

A hopeless babe who cried

Was God Incarnate and man deified

Chorus

Because the fall did devastate

Creator must now recreate

So to take our sin

Was made like us so we could be like him

Repeat Chorus

Posted by Tony Byrne at 12/25/2005 0 comments

Labels: Holidays

December 14, 2005

Alvin Plantiga’s Humorous View on Fundamentalism

We must first look into the use of this term “fundamentalist.” On the most common contemporary academic use of the term, it is a term of abuse or disapprobation, rather like “son of a bitch,” more exactly “sonovabitch,” or perhaps still more exactly (at least according to those authorities who look to the Old West as normative on matters of pronunciation) “sumbitch.” When the term is used in this way, no definition of it is ordinarily given. (If you called someone a sumbitch, would you feel obliged first to define the term?) Still, there is a bit more to the meaning of “fundamentalist” (in this widely current use): it isn’t simply a term of abuse. In addition to its emotive force, it does have some cognitive content, and ordinarily denotes relatively conservative theological views. That makes it more like “stupid sumbitch” (or maybe “fascist sumbitch”?) than “sumbitch” simpliciter. It isn’t exactly like that term either, however, because its cognitive content can expand and contract on demand; its content seems to depend on who is using it. In the mouths of certain liberal theologians, for example, it tends to denote any who accept traditional Christianity, including Augustine, Aquinas, Luther, Calvin, and Barth; in the mouths of devout secularists like Richard Dawkins or Daniel Dennett, it tends to denote anyone who believes there is such a person as God. The explanation is that the term has a certain indexical element: its cognitive content is given by the phrase “considerably to the right, theologically speaking, of me and my enlightened friends.” The full meaning of the term, therefore (in this use), can be given by something like “stupid sumbitch whose theological opinions are considerably to the right of mine.”Alvin Plantinga, Warranted Christian Belief (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000), 244–45.

Posted by Tony Byrne at 12/14/2005 0 comments

Labels: Uncategorized

Jonathan Edwards (1703–1758) on Heaven

Every saint in heaven is as a flower in the garden of God, and holy love is the fragrance and sweet odor that they all send forth, and with which they fill the bowers of that paradise above. Every soul there is as a note in some concert of delightful music, that sweetly harmonizes with every other note, and all together blend in the most rapturous strains in praising God and the Lamb forever.The New Dictionary of Thoughts, 267.

On degrees of blessedness, he said:

The saints are like so many vessels of different sizes cast into a sea of happiness where every vessel is full: this is eternal life, for a man ever to have his capacity filled.Works 2:630. Also quoted in John Gerstner's book, Jonathan Edwards: A Mini-Theology (Wheaton, IL: Tyndale, 1987), 113.

…to pretend to describe the excellence, the greatness or duration of the happiness of heaven by the most artful composition of words would be but to darken and cloud it, to talk of raptures and ecstacies, joy and singing, is but to set forth very low shadows of the reality, and all we can say by our best rhetoric is really and truly, vastly below what is but the bare and naked truth, and if St. Paul who had seen them, thought it but in vain to endeavor to utter it much less shall we pretend to do it, and the Scriptures have gone as high in the descriptions of it as we are able to keep pace with it in our imaginations and conception…John Gerstner, Jonathan Edwards on Heaven and Hell (Soli Deo Gloria, 1998), 12–13.

Posted by Tony Byrne at 12/14/2005 0 comments

Labels: Heaven, Jonathan Edwards

December 9, 2005

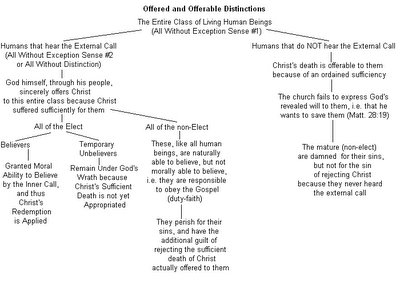

Offered and Offerable Distinctions

This is no easy task when so called "Calvinists" themselves resist it. May the following chart contribute to the restoration of the early view of the Reformers, and to the glory of God:

A few notes on the chart above:

Posted by Tony Byrne at 12/09/2005 0 comments

Labels: The Gospel Offer

J. C. Ryle (1816–1900) on John 6:32 and Christ's Redemption

The expression, "giveth you," must not be supposed to imply actual reception on the part of the Jews. It rather means "giving" in the sense of "offering" for acceptance a thing which those to whom it is offered may not receive.—It is a very remarkable saying, and one of those which seems to me to prove unanswerably that Christ is God's gift to the whole world,—that His redemption was made for all mankind,—that He died for all,—and is offered to all. It is like the famous texts, "God so loved the world that he gave his only begotten Son" (John iii. 16); and, "God hath given to us eternal life, and this life is in his Son." (1 John v. 11.) It is a gift no doubt which is utterly thrown away, like many other gifts of God to man, and is profitable to none but those that believe. But that God nevertheless does in a certain sense actually "give" His Son, as the true bread from heaven, even to the wicked and unbelieving, appears to me incontrovertibly proved by the words before us. It is a remarkable fact that Erskine, the famous Scotch seceder, based his right to offer Christ to all, on these very words, and defended himself before the General Assembly of the Kirk of Scotland on the strength of them. He asked the Moderator to tell him what Christ meant when He said, "My Father giveth you the true bread from heaven,"—and got no answer. The truth is, I venture to think, that the text cannot be answered by the advocates of an extreme view of particular redemption. Fairly interpreted, the words mean that in some sense or another the Father does actually "give" the Son to those who are not believers. They warrant preachers and teachers in making a wide, broad, full, free, unlimited offer of Christ to all mankind without exception.Ryle's Expository Thoughts on the Gospel of John (Grand Rapids: Baker, 1979), 3:364.

Even Hutcheson, the Scotch divine, though a strong advocate of particular redemption, remarks,—"Even such as are, at present, but carnal and unsound, are not secluded from the offer of Christ; but upon right terms may expect that He will be gifted to them.

Posted by Tony Byrne at 12/09/2005 1 comments

Labels: J. C. Ryle, John 3:16, John 6:32, The Atonement

December 6, 2005

The Truth Doesn't Change

lse, self-referentially absurd, and anti-Christian. Let's quickly dismiss the foolish idea that everything changes. One could refute it by submitting various counter-factuals, or things that do not change. Or, one could be like David and cut off the head of this stupid Goliath with his own sword. If one asserts the proposition "everything changes," then one may ask if that principle itself changes. If X stands for the principle that everything changes, then one may ask if X itself changes?

lse, self-referentially absurd, and anti-Christian. Let's quickly dismiss the foolish idea that everything changes. One could refute it by submitting various counter-factuals, or things that do not change. Or, one could be like David and cut off the head of this stupid Goliath with his own sword. If one asserts the proposition "everything changes," then one may ask if that principle itself changes. If X stands for the principle that everything changes, then one may ask if X itself changes? agon is red." Someone might say that this is relative and illustrates that the truth changes, because the color of the dragon may change under different lighting conditions, or to those color-blind. What they fail to understand is the true nature of the proposition. As I said, I was the one uttering the proposition. The proposition can be clarified by saying, "Tony said the dragon is red." Now, I am not saying that everyone sees the dragon as red when I utter the proposition, so the redness is person sensitive. The proposition is actually, "Tony is being appeared to redly when viewing this dragon." Not only that, one needs to further clarify the proposition because it is time sensitive when uttered. I am typing this at 6:30 am on December 6th, 2005. The true nature of the proposition is this, "Tony is being appeared to redly when viewing this dragon at 6:30am on December 6th, 2005." We might even clarify the location by saying, "Tony is being appeared to redly when viewing this dragon on his computer at 6:30am on December 6th, 2005 in his bedroom in Irving, Texas."

agon is red." Someone might say that this is relative and illustrates that the truth changes, because the color of the dragon may change under different lighting conditions, or to those color-blind. What they fail to understand is the true nature of the proposition. As I said, I was the one uttering the proposition. The proposition can be clarified by saying, "Tony said the dragon is red." Now, I am not saying that everyone sees the dragon as red when I utter the proposition, so the redness is person sensitive. The proposition is actually, "Tony is being appeared to redly when viewing this dragon." Not only that, one needs to further clarify the proposition because it is time sensitive when uttered. I am typing this at 6:30 am on December 6th, 2005. The true nature of the proposition is this, "Tony is being appeared to redly when viewing this dragon at 6:30am on December 6th, 2005." We might even clarify the location by saying, "Tony is being appeared to redly when viewing this dragon on his computer at 6:30am on December 6th, 2005 in his bedroom in Irving, Texas."Posted by Tony Byrne at 12/06/2005 0 comments

Labels: Uncategorized

December 2, 2005

Upcoming John Frame Books

9. What works can we expect from you in the future?

I have completed Doctrine of the Christian Life, the third volume of my Theology of Lordship series. I expect that book to be published in two volumes by P&R. At least the first volume should be available in 2006. Also in 2006 P&R is planning to publish my Salvation Belongs to the Lord, a mini-systematic theology. Now I’m working on Doctrine of the Word of God, the last volume planned for the Lordship series. That will take a lot of time to research and write. Don’t expect it before maybe three or four years.

Posted by Tony Byrne at 12/02/2005 1 comments

Labels: John Frame