51. Resolved, that I will act so, in every respect, as I think I shall wish I had done, if I should at last be damned. July 8, 1723.

55. Resolved, to endeavor to my utmost to act as I can think I should do, if I had already seen the happiness of heaven, and hell torments. July 8, 1723.

December 31, 2005

Serious Resolutions

Posted by Tony Byrne at 12/31/2005 4 comments

Labels: Jonathan Edwards

December 30, 2005

On Essential Doctrines and the Difference Between Affirmation and Denial

A square has four sides, and an object that does not have four sides is not a square. In other words, having four sides is essential to squareness. A square's color may change, but the color is a non-essential quality.

A square has four sides, and an object that does not have four sides is not a square. In other words, having four sides is essential to squareness. A square's color may change, but the color is a non-essential quality.Posted by Tony Byrne at 12/30/2005 3 comments

Labels: Essentials, Logic

December 25, 2005

Christmas Thoughts

When the Father long to show

The love He wanted us to know

He sent His only Son and so

Became a holy embryo

Chorus

That is the Mystery

More than you can see

Give up on your pondering

And fall down on your knees

A fiction as fantastic and wild

A mother made by her own child

A hopeless babe who cried

Was God Incarnate and man deified

Chorus

Because the fall did devastate

Creator must now recreate

So to take our sin

Was made like us so we could be like him

Repeat Chorus

Posted by Tony Byrne at 12/25/2005 0 comments

Labels: Holidays

December 14, 2005

Alvin Plantiga’s Humorous View on Fundamentalism

We must first look into the use of this term “fundamentalist.” On the most common contemporary academic use of the term, it is a term of abuse or disapprobation, rather like “son of a bitch,” more exactly “sonovabitch,” or perhaps still more exactly (at least according to those authorities who look to the Old West as normative on matters of pronunciation) “sumbitch.” When the term is used in this way, no definition of it is ordinarily given. (If you called someone a sumbitch, would you feel obliged first to define the term?) Still, there is a bit more to the meaning of “fundamentalist” (in this widely current use): it isn’t simply a term of abuse. In addition to its emotive force, it does have some cognitive content, and ordinarily denotes relatively conservative theological views. That makes it more like “stupid sumbitch” (or maybe “fascist sumbitch”?) than “sumbitch” simpliciter. It isn’t exactly like that term either, however, because its cognitive content can expand and contract on demand; its content seems to depend on who is using it. In the mouths of certain liberal theologians, for example, it tends to denote any who accept traditional Christianity, including Augustine, Aquinas, Luther, Calvin, and Barth; in the mouths of devout secularists like Richard Dawkins or Daniel Dennett, it tends to denote anyone who believes there is such a person as God. The explanation is that the term has a certain indexical element: its cognitive content is given by the phrase “considerably to the right, theologically speaking, of me and my enlightened friends.” The full meaning of the term, therefore (in this use), can be given by something like “stupid sumbitch whose theological opinions are considerably to the right of mine.”Alvin Plantinga, Warranted Christian Belief (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000), 244–45.

Posted by Tony Byrne at 12/14/2005 0 comments

Labels: Uncategorized

Jonathan Edwards (1703–1758) on Heaven

Every saint in heaven is as a flower in the garden of God, and holy love is the fragrance and sweet odor that they all send forth, and with which they fill the bowers of that paradise above. Every soul there is as a note in some concert of delightful music, that sweetly harmonizes with every other note, and all together blend in the most rapturous strains in praising God and the Lamb forever.The New Dictionary of Thoughts, 267.

On degrees of blessedness, he said:

The saints are like so many vessels of different sizes cast into a sea of happiness where every vessel is full: this is eternal life, for a man ever to have his capacity filled.Works 2:630. Also quoted in John Gerstner's book, Jonathan Edwards: A Mini-Theology (Wheaton, IL: Tyndale, 1987), 113.

…to pretend to describe the excellence, the greatness or duration of the happiness of heaven by the most artful composition of words would be but to darken and cloud it, to talk of raptures and ecstacies, joy and singing, is but to set forth very low shadows of the reality, and all we can say by our best rhetoric is really and truly, vastly below what is but the bare and naked truth, and if St. Paul who had seen them, thought it but in vain to endeavor to utter it much less shall we pretend to do it, and the Scriptures have gone as high in the descriptions of it as we are able to keep pace with it in our imaginations and conception…John Gerstner, Jonathan Edwards on Heaven and Hell (Soli Deo Gloria, 1998), 12–13.

Posted by Tony Byrne at 12/14/2005 0 comments

Labels: Heaven, Jonathan Edwards

December 9, 2005

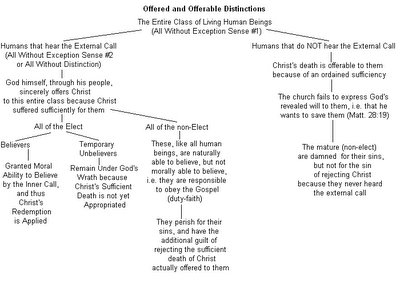

Offered and Offerable Distinctions

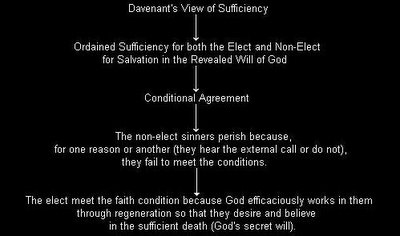

This is no easy task when so called "Calvinists" themselves resist it. May the following chart contribute to the restoration of the early view of the Reformers, and to the glory of God:

A few notes on the chart above:

Posted by Tony Byrne at 12/09/2005 0 comments

Labels: The Gospel Offer

J. C. Ryle (1816–1900) on John 6:32 and Christ's Redemption

The expression, "giveth you," must not be supposed to imply actual reception on the part of the Jews. It rather means "giving" in the sense of "offering" for acceptance a thing which those to whom it is offered may not receive.—It is a very remarkable saying, and one of those which seems to me to prove unanswerably that Christ is God's gift to the whole world,—that His redemption was made for all mankind,—that He died for all,—and is offered to all. It is like the famous texts, "God so loved the world that he gave his only begotten Son" (John iii. 16); and, "God hath given to us eternal life, and this life is in his Son." (1 John v. 11.) It is a gift no doubt which is utterly thrown away, like many other gifts of God to man, and is profitable to none but those that believe. But that God nevertheless does in a certain sense actually "give" His Son, as the true bread from heaven, even to the wicked and unbelieving, appears to me incontrovertibly proved by the words before us. It is a remarkable fact that Erskine, the famous Scotch seceder, based his right to offer Christ to all, on these very words, and defended himself before the General Assembly of the Kirk of Scotland on the strength of them. He asked the Moderator to tell him what Christ meant when He said, "My Father giveth you the true bread from heaven,"—and got no answer. The truth is, I venture to think, that the text cannot be answered by the advocates of an extreme view of particular redemption. Fairly interpreted, the words mean that in some sense or another the Father does actually "give" the Son to those who are not believers. They warrant preachers and teachers in making a wide, broad, full, free, unlimited offer of Christ to all mankind without exception.Ryle's Expository Thoughts on the Gospel of John (Grand Rapids: Baker, 1979), 3:364.

Even Hutcheson, the Scotch divine, though a strong advocate of particular redemption, remarks,—"Even such as are, at present, but carnal and unsound, are not secluded from the offer of Christ; but upon right terms may expect that He will be gifted to them.

Posted by Tony Byrne at 12/09/2005 1 comments

Labels: J. C. Ryle, John 3:16, John 6:32, The Atonement

December 6, 2005

The Truth Doesn't Change

lse, self-referentially absurd, and anti-Christian. Let's quickly dismiss the foolish idea that everything changes. One could refute it by submitting various counter-factuals, or things that do not change. Or, one could be like David and cut off the head of this stupid Goliath with his own sword. If one asserts the proposition "everything changes," then one may ask if that principle itself changes. If X stands for the principle that everything changes, then one may ask if X itself changes?

lse, self-referentially absurd, and anti-Christian. Let's quickly dismiss the foolish idea that everything changes. One could refute it by submitting various counter-factuals, or things that do not change. Or, one could be like David and cut off the head of this stupid Goliath with his own sword. If one asserts the proposition "everything changes," then one may ask if that principle itself changes. If X stands for the principle that everything changes, then one may ask if X itself changes? agon is red." Someone might say that this is relative and illustrates that the truth changes, because the color of the dragon may change under different lighting conditions, or to those color-blind. What they fail to understand is the true nature of the proposition. As I said, I was the one uttering the proposition. The proposition can be clarified by saying, "Tony said the dragon is red." Now, I am not saying that everyone sees the dragon as red when I utter the proposition, so the redness is person sensitive. The proposition is actually, "Tony is being appeared to redly when viewing this dragon." Not only that, one needs to further clarify the proposition because it is time sensitive when uttered. I am typing this at 6:30 am on December 6th, 2005. The true nature of the proposition is this, "Tony is being appeared to redly when viewing this dragon at 6:30am on December 6th, 2005." We might even clarify the location by saying, "Tony is being appeared to redly when viewing this dragon on his computer at 6:30am on December 6th, 2005 in his bedroom in Irving, Texas."

agon is red." Someone might say that this is relative and illustrates that the truth changes, because the color of the dragon may change under different lighting conditions, or to those color-blind. What they fail to understand is the true nature of the proposition. As I said, I was the one uttering the proposition. The proposition can be clarified by saying, "Tony said the dragon is red." Now, I am not saying that everyone sees the dragon as red when I utter the proposition, so the redness is person sensitive. The proposition is actually, "Tony is being appeared to redly when viewing this dragon." Not only that, one needs to further clarify the proposition because it is time sensitive when uttered. I am typing this at 6:30 am on December 6th, 2005. The true nature of the proposition is this, "Tony is being appeared to redly when viewing this dragon at 6:30am on December 6th, 2005." We might even clarify the location by saying, "Tony is being appeared to redly when viewing this dragon on his computer at 6:30am on December 6th, 2005 in his bedroom in Irving, Texas."Posted by Tony Byrne at 12/06/2005 0 comments

Labels: Uncategorized

December 2, 2005

Upcoming John Frame Books

9. What works can we expect from you in the future?

I have completed Doctrine of the Christian Life, the third volume of my Theology of Lordship series. I expect that book to be published in two volumes by P&R. At least the first volume should be available in 2006. Also in 2006 P&R is planning to publish my Salvation Belongs to the Lord, a mini-systematic theology. Now I’m working on Doctrine of the Word of God, the last volume planned for the Lordship series. That will take a lot of time to research and write. Don’t expect it before maybe three or four years.

Posted by Tony Byrne at 12/02/2005 1 comments

Labels: John Frame

November 27, 2005

Thomas the Day Dreamer (Part 2)

Basic to the religion’s doctrine was the conflicting dualism between the realm of God, represented by light and by spiritual enlightenment, and the realm of Satan, symbolized by darkness and by the world of material things. To account for the existence of evil in a world created by God, Mani posited a primal struggle in which the forces of Satan separated from God; humanity, composed of matter, that which belongs to Satan, but infused with a modicum of godly light, was a product of this struggle, and was a paradigm of the eternal war between the forces of light and those of darkness. Christ, the ideal, light-clad soul, could redeem for each person that portion of light God had allotted. Light and dark were seen to be commingled in our present age as good and evil, but in the last days each would return to its proper, separate realm, as they were in the beginning. The Christian notion of the Fall and of personal sin was repugnant to the Manichees; they felt that the soul suffered not from a weak and corrupt will but from contact with matter. Evil was a physical, not a moral, thing; a person’s misfortunes were miseries, not sins.Chesterton describes a social situation in which Thomas is participating in a royal banquet. He was courteous to all that spoke with him, but he spoke little. Rather than thinking about the noisy clatter around him, his mind was meditating on how to refute Manichaeism. Chesterton tells the story this way:

There is one casual anecdote about St. Thomas Aquinas which illuminates him like a lightening-flash, not only without but within. For it not only shows him as a character, and even as a comedy character, and shows the colours of his period and social background; but also, as if for an instant, makes a transparency of his mind. It is a trivial incident which occurred one day, when he was reluctantly dragged from his work, and we might almost say from his play. For both were for him found in the unusual hobby of thinking, which is for some men a thing much more intoxicating than mere drinking. He had declined any number of society invitations, to the courts of kings and princes, not because he was unfriendly, for he was not; but because he was always glowing within with the really gigantic plans of exposition and argument which filled his life. On one occassion, however, he was invited to the court of King Louis IX of France, more famous as the great St. Louis; and for some reason or other, the Dominican authorities of his Order told him to accept; so he immediately did so, being an obedient friar even in his sleep; or rather in his permanent trance of reflection.G. K. Chesterton, Saint Thomas Aquinas "The Dumb Ox" (New York: Doubleday, 1956), 74–78.

It is a real case against conventional hagiography that it sometimes tends to make all saints seem to be the same. Whereas in fact no men are more different than saints; not even murderers. And there could hardly be a more complete contrast, given the essentials of holiness, than between St. Thomas and St. Louis. St. Louis was born a knight and a king; but he was one of those men in whom a certain simplicity, combined with courage and activity, makes it natural, and in a sense easy, to fulfill directly and promptly any duty or office, however official. He was a man in whom holiness and healthiness had no quarrel; and their issue was in action. He did not go in for thinking much, in the sense of theorising much. But, even in theory, he had that sort of presence of mind, which belongs to the rare and really practical man when he has to think. He never said the wrong thing; and he was orthodox by instinct. In the old pagan proverb about kings being philosophers or philosophers kings, there was a certain miscalculation, connected with a mystery that only Christianity could reveal. For while it is possible for a king to wish very much to be a saint, it is not possible for a saint to wish very much to be a king. A good man will hardly be always dreaming of being a great monarch; but, such is the liberality of the Church, that she cannot forbid even a great monarch to dream of being a good man. But Louis was a straightforward soldierly sort of person who did not particularly mind being a king, any more than he would have minded being a captain or a sergeant or any other rank in his army. Now a man like St. Thomas would definitely dislike being a king, or being entangled with the pomp and politics of kings; not only his humility, but a sort of subconscious fastidiousness and fine dislike of futility, often found in leisurely and learned men with large minds, would really have prevented him making contact with the complexity of court life. Also, he was anxious all his life to keep out of politics; and there was no political symbol more striking, or in a sense more challenging, at that moment, than the power of the King in Paris.

Paris was truly at that time an aurora borealis; a Sunrise in the North. We must realise that lands much nearer to Rome had rotted with paganism and pessimism and Oriental influences of which the most respectable was that of Mahound. Provence and all the South had been full of a fever of nihilism or negative mysticism, and from Northern France had come the spears and swords that swept away the unchristian thing. In Northern France also sprang up that splendour of building that shines like swords and spears: the first spires of the Gothic. We talk now of grey Gothic buildings; but they must have been very different when they went up white and gleaming into the northern skies, partly picked out with gold and bright colours; a new flight of architecture, as startling as flying ships. The new Paris ultimately left behind by St. Louis must have been a thing white like lilies and splendid as the oriflamme. It was the beginning of the great new thing: the nation of France, which was to pierce and overpower the old quarrel of Pope and Emperor in the lands from which Thomas came. But Thomas came very unwillingly, and, if we may say it of so kindly a man, rather sulkily. As he entered Paris, they showed him from the hill that splendour of new spires beginning, and somebody said something like, "How grand it must be to own all this." And Thomas Aquinas only muttered, "I would rather have that Chrysostom MS. I can't get hold of."

Somehow they steered that reluctant bulk of reflection to a seat in the royal banquet hall; and all that we know of Thomas tells us that he was perfectly courteous to those who spoke to him, but spoke little, and was soon forgotten in the most brilliant and noisy clatter in the world: the noise of French talking. What the Frenchmen were talking about we do not know; but they forgot all about the large fat Italian in their midst, and it seems only too possible that he forgot all about them. Sudden silences will occur even in French conversation; and in one of these interruption came. There had long been no word or motion in that huge heap of black and white weeds, like motley in the mourning, which marked him as a mendicant friar out of the streets, and contrasted with all the colours and patters and quarterings of that first and freshest dawn of chivalry and heraldry. The triangular shields and pennons and pointed spears, the triangular swords of the Crusade, the pointed windows and the conical hoods, repeated everywhere that fresh French medieval spirit that did, in every sense, come to the point. But the colours of the coats were gay and varied with little to rebuke their richness; for St. Louis, who had himself a special quality of coming to the point, had said to his courtiers, "Vanity should be avoided; but every man should dress well, in the manner of his rank, that his wife may the more easily love him."

And then suddenly the goblets leapt and rattled on the board and the great table shook, for the friar had brought down his huge fist like a club of stone, with a crash that startled everyone like an explosion; and had cried out in a strong voice, but like a man in the grip of a dream, "And that will settle the Manichees!"

The palace of a king, even when it is the palace of a saint, has its conventions. A shock thrilled through the court, and every one felt as if the fat friar from Italy had thrown a plate at King Louis, or knocked his crown sideways. They all looked timidly at the terrible seat, that was for a thousand years the throne of the Capets; and man there were presumably prepared to pitch the big black-robed beggarman out of the window. But St. Louis, simple as he seemed, was no mere medieval fountain of honour or even fountain of mercy; but also the fountain of two eternal rivers; the irony and the courtesy of France. And he turned to his secretaries, asking them in a low voice to take their tablets round to the seat of the absent-minded controversialist, and take a note of the argument that had just occurred to him; because it must be a very good one and he might forget it. I have paused upon this anecdote, first, as has been said, because it is the one which gives us the most vivid snapshot of a great medieval character; indeed of two great medieval characters. But it is also specially fitted to be taken as a type or a turning-point, because of the glimpse it gives of the man's main preoccupation; and the sort of thing that might have been found in his thoughts, if they had been thus suprised at any moment by a philosophical eavesdropper or through a psychological keyhole. It was not for nothing that he was still brooding, even in the white court of St. Louis, upon the dark cloud of the Manichees.

Posted by Tony Byrne at 11/27/2005 0 comments

Labels: Aquinas, Meditation

November 26, 2005

Thomas the Day Dreamer (Part 1)

G. K. Chesterton was an excellent writer, and this is very apparent in his book on Thomas Aquinas, aka "The Dumb Ox". I love the way Chesterton describes Thomas as one who was sometimes "absent-minded" and a "day dreamer." I suppose the following quote stands out to me because I tend to day dream when I am around family members during the holidays. Our holiday practices seem to be like modern shells devoid of their pre-modern substance. We go through the motions and externals without thinking about the significance of what we are doing, or about the transcendent origins of the truths contained in the traditions.

G. K. Chesterton was an excellent writer, and this is very apparent in his book on Thomas Aquinas, aka "The Dumb Ox". I love the way Chesterton describes Thomas as one who was sometimes "absent-minded" and a "day dreamer." I suppose the following quote stands out to me because I tend to day dream when I am around family members during the holidays. Our holiday practices seem to be like modern shells devoid of their pre-modern substance. We go through the motions and externals without thinking about the significance of what we are doing, or about the transcendent origins of the truths contained in the traditions.

Since no one in my immediate family is a Christian, it is normal for the conversations to be largely trivial and uninteresting. You might call the conversations "small talk." I understand how some may interpret my descriptions as being condescending, but they are not. They are capable of understanding anything that I can, but they don't want to.

Most people, particularly in my culture and family context, engage in small talk to avoid potentially painful thinking (topics that would trouble their conscience), or thinking that may disrupt "peaceful" relationships. It seems as if conversations are deliberately kept at a superficial level so that everyone can just get along and not be troubled by ultimate questions. Occasionally I try to tactfully introduce topics concerning ideas, but usually things quickly return to a focus on people, events and other trivialities as we mindlessly sit in front of the television. So, for the most part, I find myself going through the motions of our cultural activities while day dreaming about ideas. I tend to be absent-minded in this regard. Chesterton's descriptions of Thomas have helped me to understand a little bit about myself.

Here is an excerpt from Chesterton's book that I think is outstanding:

The pictures of St. Thomas, though many of them painted long after his death, are all obviously pictures of the same man. He rears himself defiantly, with the Napoleonic head and the dark bulk of body, in Raphael's "Dispute About the Sacrament." A portrait by Ghirlandajo emphasises a point which specially reveals what may be called the neglected Italian quality in the man. It also emphasises points that are very important in the mystic and the philosopher. It is universally attested that Aquinas was what is commonly called an absent-minded man. That type has often been rendered in painting, humorous or serious; but almost always in one of two or three conventional ways. Sometimes the expression of the eyes is merely vacant, as if absent-mindedness did really mean a permanent absence of mind. Sometimes it is rendered more respectfully as a wistful expression, as of one yearning for something afar off, that he cannot see and can only faintly desire. Look at the eyes in Ghirlandajo's portrait of St. Thomas; and you will see a sharp difference. While the eyes are indeed completely torn away from the immediate surroundings, so that the pot of flowers above the philosopher's head might fall on it without attracting his attention, they are not in the least wistful, let alone vacant. There is kindled in them a fire of instant inner excitement; they are vivid and very Italian eyes. The man is thinking about something; and something that has reached a crisis; not about nothing or about anything; or, what is almost worse, about everything. There must have been that smouldering vigilance in his eyes, the moment before he smote the table and startled the banquet all of the King.G. K. Chesterton, Saint Thomas Aquinas "The Dumb Ox" (New York: Doubleday, 1956), 98–101.

Of the personal habits that go with the personal physique, we have also a few convincing and confirming impressions. When he was not sitting still, reading a book, he walked round and round the cloisters and walked fast and even furiously, a very characteristic action of men who fight their battles in the mind. Whenever he was interrupted, he was very polite and more apologetic than the apologizer. But there was that about him, which suggested that he was rather happier when he was not interrupted. He was ready to stop his truly Peripatetic tramp: but we feel that when he resumed it, he walked all the faster.

All this suggests that his superficial abstraction, that which the world saw, was of a certain kind. It will be well to understand the quality, for there are several kinds of absence of mind, including that of some pretentious poets and intellectuals, in whom the mind has never been noticeably present. There is the abstraction of the contemplative, whether he is the true sort of Christian contemplative, who is contemplating Something, or the wrong sort of Oriental contemplative, who is contemplating Nothing. Obviously St. Thomas was not a Buddhist mystic; but I do not think his fits of abstraction were even those of a Christian mystic. If he has trances of true mysticism, he took jolly good care that they should not occur at other people's dinner-tables. I think he had the sort of bemused fit, which really belongs to the practical man rather than the entirely mystical man. He uses the recognized distinction between the active life and the contempletive life, but in the cases concerned here, I think even his contemplative life was an active life. It had nothing to do with his higher life, in the sense of ultimate sanctity. It rather reminds us that Napoleon would fall into a fit of apparent boredom at the Opera, and afterwards confess that he was thinking how he could get three army corps at Frankfurt to combine with two army corps at Cologne. So, in the case of Aquinas, if his daydreams were dreams, they were dreams of day; and dreams of the day of battle. If he talked to himself, it was because he was arguing with somebody else. We can put it another way, by saying that his daydreams, like the dreams of a dog, were dreams of hunting; of pursuing the error as well as pursuing the truth; of following all the twists and turns of evasive falsehood, and tracking it at last to its lair in hell. He would have been the first to admit that the erroneous thinker would probably be more surprised to learn where his thought came from, than anybody else to discover where it went to. But this notion of pursuing he certainly had, and it was the beginning of a thousand mistakes and misunderstandings that pursuing is called in Latin Persecution. Nobody had less than he had of what is commonly called the temper of a persecutor; but he had the quality which in desperate times is often driven to persecute; and that is simply the sense that everything lives somewhere, and nothing dies unless it dies in its own home. That he did sometimes, in this sense, "urge in dreams the shadowy chase" even in broad daylight, is quite true. But he was an active dreamer, if not what is commonly called a man of action; and in that chase he was truly to be counted among the domini canes; and surely the mightiest and most magnanimous of the Hounds of Heaven.

See also Thomas the Day Dreamer (Part 2)

Posted by Tony Byrne at 11/26/2005 1 comments

Labels: Aquinas, Meditation

November 24, 2005

A Few Quotes on Gratitude

Posted by Tony Byrne at 11/24/2005 0 comments

Labels: Holidays

November 22, 2005

Noise and Meditation

The author, Erik Lokkesmoe, writing as if he were C. S. Lewis's senior demon named Screwtape, says to Wormwood (a demon in training):

But oh, how dreadful it is if they do notice and, worse yet, begin to reject the delightful opiates we offer. An hour’s walk or an evening alone can be hazardous. Even a drive with a broken radio carries risk. Peace and quietude, after all, are the Enemy's handiwork. He waits patiently for them in the stillness, whispering for them to rest or ponder or, dare I say that repulsive word, meditate.

I trust you understand what is at stake. If allowed to contemplate the empty pursuits and hollow activity that often fill their days, there is no telling what horrific changes they may make in their lives. As long as the volume is high and the lights are flashing, there is little danger of this. But when allowed to face things as they really are, stripped of the comfort provided by our dizzying distractions, our subjects often choose against our ways.

This kind of activity, or rather inactivity, is a breeding ground for all manner of destructive outcomes. Rest gives them refreshed bodies and clear minds. Clarity draws them to that which we most hate: truth. In such moments their vision grows strong and purpose is rekindled. For Hell’s sake, do not let this happen!

Posted by Tony Byrne at 11/22/2005 0 comments

Labels: Meditation

November 21, 2005

John Davenant’s (1572–1641) Sufficiency Distinctions

John Davenant, “A Dissertation on the Death of Christ,” in An Exposition of the Epistle of St. Paul to the Colossians, trans. Josiah Allport, 2 vols. (London: Hamilton, Adams, and Co., 1832), 2:401–404.CHAPTER IV.

THE SECOND PROPOSITION STATED, EXPLAINED AND CONFIRMED

IN our first proposition we endeavored to shew that the death or merit of Christ was appointed by God, proposed in the holy Scriptures, and to be considered by us, as an universal remedy applicable to all men for salvation from the ordination of God. And on this account we hesitate not to assert that Christ died for all men, inasmuch as he endured death, by the merit and virtue of which all men individually who obey the Gospel may be delivered from death and obtain eternal salvation. But because some persons in such a way concede that Christ died for all men, that with the same breath they assert that he died for the elect alone, and so expound that received distinction of Divines, That he died for all sufficiently, but for the elect effectually, that they entirely extinguish the first part of the sentence; we will lay down a second proposition, which will afford an occasion of discussing that subject expressly, which we have hitherto only glanced at slightly by the way. This second proposition, therefore, shall be reduced into this form; if it is rather prolix, pardon it. The death of Christ is the universal cause of the salvation of mankind, and Christ himself is acknowledged to have died for all men sufficiently, not by reason of the mere sufficiency or of the intrinsic value, according to which the death of God is a price more than sufficient for redeeming a thousand worlds; but by reason of the Evangelical covenant confirmed with the whole human race through the merit of his death, and of the Divine ordination depending upon it, according to which, under the possible condition of faith, remission of sins and eternal life is decreed to be set before every mortal man who will believe it, on account of the merits of Christ. In handling this proposition we shall do two things. First, we shall explain some of the terms. Secondly, we shall divide our proposition into certain parts, and establish them separately by some arguments.

In the first place, therefore, is to be explained, what we mean by mere sufficiency, and what by that which is commonly admitted by Divines, That Christ died for all sufficiently. If we speak of the price of redemption, that ransom is to be acknowledged sufficient which exactly answers to the debt of the captive; or which satisfies the demand of him who has the power of liberating the captive. The equality of one thing to another, or to the demands of him who has power over the captive, constitutes what we call this mere sufficiency. This shall be illustrated by examples. Suppose my brother was detained in prison for a debt of a thousand pounds. If I have in my possession so many pounds, I can truly affirm that this money is sufficient to pay the debt of my brother, and to free him from it. But while it is not offered for him, the mere sufficiency of the thing is understood, and estimated only from the value of it, the act of offering that ransom being wanting, without which the aforesaid sufficiency effects nothing. For the same reason, if many persons should be capitally condemned for the crime of high treason, and the king himself against whom this crime was committed should agree that he would be reconciled to all for whom his son should think fit to suffer death: Now the death of the Son, according to the agreement, is appointed to be a sufficient ransom for redeeming all those for whom it should be offered. But if there should be any for whom that ransom should not be offered, as to those it has only a mere sufficiency, which is supposed from the value of the thing considered in itself, and not that which is understood from the act of offering. To these things I add, If we admit the aforesaid ransom not only to be sufficient from the equality of the one thing to the other, and from his demand, who requires nothing more from the redemption of the captives; but also to be greater and better in an indefinite degree, and to exceed all their debts, yet if there should not be added to this the intention and act of offering for certain captives, although such a ransom should be ever so copious and superabundant, considered in itself and from its intrinsic value, yet what was said of the sufficiency may be said of the superabundance, that there was a mere superabundance of the thing, but that it effected nothing as yet for the liberation of the persons aforesaid.

Now to this mere sufficiency, which regards nothing else than the equal or superabundant worth of the appointed price of redemption, I oppose another, which, for the sake of perspecuity, I shall call ordained sufficiency. This is understood when the thing which has respect to the ransom, or redemption price, is not only equivalent to, or superior in value to the thing redeemed, but also is ordained for its redemption by some wish to offer or actual offering. Thus a thousand talents laid up in the treasury of a prince are said to be a sufficient ransom to redeem ten citizens taken captive by an enemy; but if there is not an intention to offer, and an actual offering and giving these talents for those captives, or for some of them, then a mere and not an ordained sufficiency of the thing is supposed as to those person for whom it is not given. But if you add the act and intention offering them for the liberation of certain persons, then the ordained sufficiency is asserted as to them alone. Further, this ordained sufficiency of the ransom for the redemption of a captive may be twofold: Absolute; when there is such agreement between him who gives and him who receives this price of redemption for the liberation of the captives, that as soon as the price is paid, on the act of payment the captives are immediately delivered. Conditional; when the price is accepted, not that it may be paid immediately, and the captive be restored to liberty; but that he should be delivered under a condition if he should first do something or other. When we say that Christ died sufficiently for all, we do not understand the mere sufficiency of the thing with a defect of the oblation as to the greater part of mankind, but that ordained sufficiency, which has the intent and act of offering joined to it, and that for all; but with the conditional, and not the absolute ordination which we have expressed. In one word, when we affirm that Christ died for all sufficiently, we mean, That there was in the sacrifice itself a sufficiency or equivalency, yea, a superabundance of price or dignity, if it should be compared to the whole human race; that both in the offering and the accepting there was a kind of ordination, according to which the aforesaid sacrifice was offered and accepted for the redemption of all mankind. This may suffice for the explanation of the first term.

Posted by Tony Byrne at 11/21/2005 0 comments

Labels: John Davenant, Sufficiency/Efficiency

November 19, 2005

Chesterton on Courage

Rush Limbaugh recently quoted from G. K. Chesterton's book on Orthodoxy. He brought it up on Veterans' Day because it's an exposition on the idea of courage. It is a remarkable piece of writing that is worthy of our meditation. Chesterton says:

Rush Limbaugh recently quoted from G. K. Chesterton's book on Orthodoxy. He brought it up on Veterans' Day because it's an exposition on the idea of courage. It is a remarkable piece of writing that is worthy of our meditation. Chesterton says:"Paganism declared that virtue was in a balance; Christianity declared it was in a conflict: the collision of two passions apparently opposite. Of course they were not really inconsistent; but they were such that it was hard to hold simultaneously. Let us follow for a moment the clue of the martyr and the suicide; and take the case of courage. No quality has ever so much addled the brains and tangled the definitions of merely rational sages. Courage is almost a contradiction in terms. It means a strong desire to live taking the form of a readiness to die. “He that will lose his life, the same shall save it,” is not a piece of mysticism for saints and heroes. It is a piece of everyday advice for sailors or mountaineers. It might be printed in an Alpine guide or a drill book. This paradox is the whole principle of courage; even of quite earthly or quite brutal courage. A man cut off by the sea may save his life if he will risk it on the precipice.

He can only get away from death by continually stepping within an inch of it. A soldier surrounded by enemies, if he is to cut his way out, needs to combine a strong desire for living with a strange carelessness about dying. He must not merely cling to life, for then he will be a coward, and will not escape. He must not merely wait for death, for then he will be a suicide, and will not escape. He must seek his life in a spirit of furious indifference to it; he must desire life like water and yet drink death like wine. No philosopher, I fancy, has ever expressed this romantic riddle with adequate lucidity, and I certainly have not done so. But Christianity has done more: it has marked the limits of it in the awful graves of the suicide and the hero, showing the distance between him who dies for the sake of living and him who dies for the sake of dying. And it has held up ever since above the European lances the banner of the mystery of chivalry: the Christian courage, which is a disdain of death; not the Chinese courage, which is a disdain of life."

Posted by Tony Byrne at 11/19/2005 0 comments

November 17, 2005

Reply to Laura

- Tony, you are free to point out any perceived holes in this, but I had an out-of-the-blue realization pro limited atonement: If the question is what Christ's death was meant to accomplish, the propitiation of God's wrath is certainly part of the answer. If Christ died for all sinners, the fact that the non-elect are called "vessels of wrath" (Rom. 9) who are storing up God's wrath in their present rebellion seems to mean that Christ's death did not satisfy God's wrath for those who are bound for eternal punishment. How could we still say, then, that Christ died for the sins of "the world" in the sense of "every individual" and not "elect from all nations?"

Posted by Tony Byrne at 11/17/2005 0 comments

November 16, 2005

John Davenant's (1572–1641) Reply to the Double Jeopardy Issue

Objection 5. If the death of Christ be a benefit from the ordination of God, applicable to each and every man, then it may be said, that Christ made satisfaction for the sins of the whole human race. But this cannot be defended, without at the same time overthrowing the justice of God, since the idea of justice does not admit that the same sin should be punished twice. Suppose, then, that the death of Christ is a ransom, by which satisfaction was made to God for the sins of the human race, how can so many persons be called to account for the same by the justice of God, and be tormented with eternal punishment?John Davenant, “A Dissertation on the Death of Christ,” in An Exposition of the Epistle of St. Paul to the Colossians (London: Hamilton, Adams, and Co., 1832), 2:374–377.

Reply 5. As to the major proposition, we think its consequence may be safely conceded. For the orthodox Fathers boldly assert that Christ made satisfaction for the sins of the human race or all of mankind. Thus Eusebius, (Evang. Demonstr. lib. x. in the preface) It was needful that the Lamb of God should be offered as a sacrifice for the other lambs whose nature he assumed, even for the whole human race. Thus Nazianzen (Orat. 2. in Pasch.) The sacrifice of Christ is an imperishable expiation of the whole world. Thus, finally (omitting others), Cyril (Catech. 13.), He redeemed the whole world of mankind. The same form of speaking is every where made use of in the Articles of religion of our Church of England, (Art. 2, 15, 31, &c.). Thus also those speak who endeavour to limit to the utmost this death of Christ. We adduced before the testimony of the Reverend Heidelberg Divine Pareus, who freely confesses in his judgment exhibited at the Synod of Dort, The cause and matter of the passion of Christ was a feeling or sustaining of the wrath of God, incensed by the sin, not of some men, but of the whole human race. A little afterwards, The whole of sin and of the wrath of God against it, is affirmed to have been borne by Christ. Nor ought this to appear unsound, since this universal redemption, satisfaction, or expiation performed by the death of Christ, brings nothing more than an universal cause of salvation to be confirmed and granted to the human race by the Divine ordination; the benefit of which every individual may enjoy through faith required by the Gospel. We therefore call Christ the Redeemer of the world, and teach that he made satisfaction for the sins not of some, but of the whole world, not because that on account of the payment of this price for the sins of the human race, all mankind individually are to be immediately delivered from captivity and death, but because by virtue of the payment of this price, all men individually may and ought to be delivered from death, and, in fact, are to be delivered according to the tenor of the evangelical covenant, that is, if they repent and believe in this Redeemer.

To what is further urged, That it is contrary to justice to receive satisfaction or a ransom for the sins of the whole human race, and yet not to deliver them all from the punishment of their sins, but, notwithstanding this satisfaction, to adjudge many to eternal torments; I answer, That this would indeed be most unjust, if we ourselves had paid this price to God, or if our Surety, Jesus Christ, had so offered to God his blood as a satisfactory price, that without any other intervening condition, all men should be immediately absolved through the offering of the oblation made by him; or, finally, if God himself had covenanted with Christ when he died, that he would give faith to every individual, and all those other things which regard the infallible application of this sacrifice which was offered up for the human race. But since God himself of his own accord provided that this price should be paid to himself, it was in his own power to annex conditions, which being performed, this death should be advantageous to any man, not being performed it should not profit any man. Therefore no injustice is done to those persons who are punished by God after the ransom was accepted for the sins of the human race, because they offered nothing to God as a satisfaction for their sins, nor performed that condition, without the performance of which God willed not that this satisfactory price should benefit any individual. Nor, moreover, ought this to be thought an injustice to Christ the Mediator. For he so was willing to die for all, and to pay to the Father the price of redemption for all, that at the same time he willed not that every individual in any way whatsoever, but that all, as soon as they believed in him, should be absolved from the guilt of their sins. Lastly, Christ, in offering himself in sacrifice to God the Father in order to expiate the sins of the world, nevertheless submitted to the good pleasure of the Father the free distribution and application of his merits, neither was any agreement entered into between the Father and the Son, by which God is bound to effect that this death of Christ, which, from the ordination of God, is applicable to all under the condition of faith, should become applied to all by the gift of faith. We ought not, therefore, to deny that the offering of Christ once made is a perfect satisfaction for the sins, not of some men only, but of all; yet so that he who is simply said to have died for all, promises remission of sin through his death and salvation conditionally, and will perform it to those alone who believe. We will illustrate all these things by a similitude; Suppose that a number of men were cast into prison by a certain King on account of a great debt, or that they were condemned to suffer death for high treason; but that the King himself procured that his own Son should discharge this debt to the last farthing; or should substitute himself as guilty in the room of those traitors, and should suffer the punishment due to them all, this condition being at the same time promulgated both by the King and his Son, That none should be absolved or liberated except those only who should acknowledge the King's Son for their Lord and serve him: These things being so determined, I inquire, if those who persist in disobedience and rebellion against the King's Son should not be delivered, would any charge of injustice be incurred, because after this ransom had been paid, their own debts should be exacted from many, or after the punishment endured by the Son, these rebels should nevertheless be punished? By no means; because the payment of the just price, and the enduring of the punishment was ordained to procure remission for every one under the condition of obedience, and not otherwise. I shall add no more; it will be easy to accommodate all these things to our present purpose.

For other responses to the Double Jeopardy argument by Reformed thinkers such as Edward Polhill, Charles Hodge, R. L. Dabney, W. G. T. Shedd, Curt Daniel and Neil Chambers, go here:

Double Jeopardy?

Posted by Tony Byrne at 11/16/2005 0 comments

Labels: Double Payment, John Davenant

November 15, 2005

Media, Music and the Meaning of Life

Posted by Tony Byrne at 11/15/2005 0 comments

Labels: Audio/Video

November 9, 2005

More for the Audiophiles

Posted by Tony Byrne at 11/09/2005 0 comments

Labels: Audio/Video

November 2, 2005

Mohler/Patterson Debate

Posted by Tony Byrne at 11/02/2005 0 comments

Labels: Audio/Video

Dabney in Audio

Posted by Tony Byrne at 11/02/2005 0 comments

Labels: Audio/Video, R. L. Dabney

October 31, 2005

John Robinson (1576–1625) and “Reformation Day”

John Robinson, pastor to the Pilgrims who sailed to the New World, has some relevant words for those speaking of a “Reformation Day.” I celebrate what the Reformers accomplished in Christ’s name in so far as their thoughts and actions correspond to scripture. However, I am not one to so sing the praises of the Reformers such that I don’t notice where they made mistakes and acted wrongly. I am grieved when I am around Christians who fall prey to Reformation propaganda to the extent that they refuse to go beyond the Reformers. This sometimes happens because they are so locked into their traditions and confessions (taking great pride in them), that they can go no further than Luther, Calvin, or their successors. These types of people may have favorite teachers that they so admire, that they will not hold anything contrary to what these men teach.

John Robinson, pastor to the Pilgrims who sailed to the New World, has some relevant words for those speaking of a “Reformation Day.” I celebrate what the Reformers accomplished in Christ’s name in so far as their thoughts and actions correspond to scripture. However, I am not one to so sing the praises of the Reformers such that I don’t notice where they made mistakes and acted wrongly. I am grieved when I am around Christians who fall prey to Reformation propaganda to the extent that they refuse to go beyond the Reformers. This sometimes happens because they are so locked into their traditions and confessions (taking great pride in them), that they can go no further than Luther, Calvin, or their successors. These types of people may have favorite teachers that they so admire, that they will not hold anything contrary to what these men teach.

John Robinson has appropriate words for such people. Speaking about his memorable charge to the departing company at Delft Haven, the following is reported:

All things being ready, Mr. Robinson observed a day of fasting and prayer with his congregation, and took his leave of the adventurers with the following truly generous and Christian exhortation:Daniel Neal, The History of the Puritans; Or, Protestant Nonconformists, 5 vols. (London: William Baynes and Son, 1822), 2:110–11. “Sed ex eo etiam fieri potest, ut maneant erorum atque superstitionum reliquiae, quod quo tempore aliqua facienda fit divini cultus, piorumque dogmatum restituio, arbitrentur non statim initio restitui omnia posse, sed primum ea tollenda esse in quibus insignis aliqua sit impietas, interjecto deinde tempore aliquo minore impedimento integram institui posse restitutionem. eventus enim multis locis docuit, plus esse difficultatis postea in tollendis reliquiis, quam fuerit initio in tollendis praecipuis erroribus: ut quum eo veniendum est praestet multo, eadem opera omnia corrigere.” Iacobo Acontio [Jacobus Acontius], Stratagematum satanae libri 8 (Amstelaedami: Apud Ioannem Ravesteynium, 1652), 330. See also E. H. Broadbent, The Pilgrim Church (Basingstoke, Hants, UK: Pickering & Inglis, 1985), 245–46.

“Brethren,

“We are now quickly to part from one another, and whether I may ever live to see your faces on earth any more, the God of heaven only knows; but whether the Lord has appointed that or no, I charge you before God and his blessed angels, that you follow me no farther than you have seen me follow the Lord Jesus Christ.

“If God reveal any thing to you, by any other instrument of his, be as ready to receive it as ever you were to receive any truth by my ministry; for I am verily persuaded, the Lord has more truth yet to break forth out of his holy word. For my part, I cannot sufficiently bewail the condition of the reformed churches, who are come to a period in religion,* and will go art present no farther than the instruments of their reformation. The Lutherans cannot be drawn to go beyond what Luther saw; whatever part of his will our God has revealed to Calvin, they will rather die than embrace it; and the Calvinists, you see, stick fast where they were left by that great man of God, who yet saw not all things.

“This is a misery much to be lamented, for though they were burning and shining lights in their times, yet they penetrated not into the whole counsel of God, but were they now living, would be as willing to embrace farther light as that which they first received. I beseech you remember, it is an article of your church-covenant, that you be ready to receive whatever truth shall be made known to you from the written word of God. Remember that, and every other article of your sacred covenant. But I must here withal exhort you to take heed what you receive as truth,—examine it, consider it, and compare it with other scriptures of truth, before you receive it; for it is not possible the Christian world should come so lately out of such thick antichristian darkness, and that perfection of knowledge should break forth at once.

“I must also advise you to abandon, avoid, and shake off, the name of Brownists; it is a mere nickname, and a brand for the making religion and the professors of it odious to the Christian World.”

_______________

* The remarks of Acontius [Giacomo Aconcio (1492–1566)] are pertinent here. “The cause (says he) that the relics of error and superstition are perpetuated is, that as often as there is any reformation of religion, either in doctrine or worship, men think that every thing is not to be immediately reformed at first, but the most distinguishing errors only are to be done away; and that when some time has intervened, the reformation will be completed with less difficulty. But the event hath, in many places, shewn that it is more difficult to remove the relics of false worship and opinions, than it was at first to subvert fundamental errors. Hence it is better to correct every thing at once.” “Sed ex eo etiam fieri potest, ut maneant errorum atque superstitionum reliquiæ,” &c. Acontii Stratagemetum Satanæ, libri octo. ed. 1652, p. 330.—ED.

Posted by Tony Byrne at 10/31/2005 0 comments

Labels: Daniel Neal, Jacob Acontius, John Robinson

October 28, 2005

The New Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia on Moïse Amyraut

E. F. Karl Müller, "Amyraut, Moïse," in The New Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia, eds. S. M. Jackson, et al. (Grand Rapids: Baker, 1951), 1:160–61.AMYRAUT, am"î-rō', MOÏSE (Lat. Moses Amyraldus): Calvinist theologian and preacher; b. at Bourgueil (27 m. w.s.w. of Tours), Touraine, 1596; d. at Saumur Jan. 8, 1664. He came of an influential family in Orleans, began the study of law at Poitiers, and received the degree of licentiate in 1616; but the reading of Calvin's Institutio turned his mind to theology. This he studied eagerly at Saumur, under Cameron, to whom he was much attached. After serving as pastor for a short time at Saint-Aignan, he was called in 1626 to succeed Jean Daillé at Saumur, and soon became prominent. The national synod held at Charenton in 1631 chose him to lay its requests before Louis XIII., on which occasion his tactful bearing attracted the attention and won the respect of Richelieu. In 1633 he was appointed professor of theology at Saumur with De la Place and Cappel, and the three raised the institution into a flourishing condition, students being attracted to it from foreign countries, especially from Switzerland. Theological novelties in their teaching, however, soon stirred up opposition, which came to little in France; but in Switzerland, where the professors were less known, it reached such a pitch that students were withdrawn, and in 1675 the Helvetic Consensus was drawn up against the Saumur innovations. Amyraut was specially attacked because his teaching on grace and predestination seemed to depart from that of the Synod of Dort, by adding a conditional universal grace to the unconditional particular.

Amyraut first published his ideas in his Traité de la prédestination (Saumur, 1634), which immediately caused great excitement. The controversy became so heated that the national synod at Alençon in 1637 had to take notice of it. Amyraut and his friend Testard were acquitted of heterodoxy, and silence was imposed on both sides. The attacks continued, however, and the question came again before the synod of Charenton in 1644-45, but with the same result. Amyraut bore himself so well under all these assaults that he succeeded in conciliating many of his opponents, even the venerable Du Moulin (1655). But at the synod of Loudun in 1659 (the last for which permission was obtained—partly through Amyraut's influence—from the crown), fresh accusations were brought, this time including Daillé, the president of the synod, because he had defended what is called "Amyraldism." This very synod, however, gave Amyraut the honorable commission to revise the order of discipline. In France the harmlessness of his teaching was generally recognized; and the controversy would soon have died out but for the continual agitation kept up abroad, especially in Holland and Switzerland.

Amyraut's doctrine has been called "hypothetical universalism"; but the term is misleading, since it might be applied also to the Arminianism which he steadfastly opposed. His main proposition is this: God wills all men to be saved, on condition that they believe—a condition which they could well fulfil in the abstract, but which in fact, owing to inherited corruption, they stubbornly reject, so that this universal will for salvation actually saves no one. God also wills in particular to save a certain number of persons, and to pass over the others with this grace. The elect will be saved as inevitably as the others will be damned. The essential point, then, of Amyraldism is the combination of real particularism with a purely ideal universalism. Though still believing it as strongly as ever, Amyraut came to see that it made little practical difference, and did not press it in his last years, devoting himself rather to non-controversial studies, especially to his system of Christian morals (La morale chrestienne, 6 vols., Saumur, 1652-60). The read significance of Amyraut's teaching lies in the fact that, while leaving unchanged the special doctrines of Calvinism, he brought to the front its ethical message and its points of universal human interest.

(E. F. Karl Müller.)

Bibliography: E. and É. Haag, La France Protestante, i. 72-80, Paris, 1846 (gives a complete list of his voluminous works); E. Saigey, in Revue de théologie, pp. 178 sqq., Paris, 1849; A. Schweizer, Tübinger theologische Jahrbücher, 1852, pp. 41 sqq., 155 sqq.

For more on Amyraut, see Brian Armstrong's book Calvinism and The Amyraut Heresy: Protestant Scholasticism and Humanism in Seventeenth-Century France.

Posted by Tony Byrne at 10/28/2005 0 comments

Labels: Amyraut/Amyraldism, Paul Testard