- Tony, you are free to point out any perceived holes in this, but I had an out-of-the-blue realization pro limited atonement: If the question is what Christ's death was meant to accomplish, the propitiation of God's wrath is certainly part of the answer. If Christ died for all sinners, the fact that the non-elect are called "vessels of wrath" (Rom. 9) who are storing up God's wrath in their present rebellion seems to mean that Christ's death did not satisfy God's wrath for those who are bound for eternal punishment. How could we still say, then, that Christ died for the sins of "the world" in the sense of "every individual" and not "elect from all nations?"

My reply:

Hi Laura,

I'm glad to see that you are spending some time thinking about the extent and intent of Christ's death :-)

It's a profound subject that relates to so many areas of theology. It provides a good opportunity to test the virtue of our thinking processes. For that reason (among many others), my "meditations" frequently touch on the issue. With that said, let me make a few points:

1) The term "limited atonement" is an imprecise way to refer to the debated issue of the nature and intent of Christ's death, even as the other TULIP words tend to be. If the doctrine is put in contrast to the Arminian view, then it's really just a doctrine that defends the logical outworking of God's special decree concerning the elect. The "limit" word refers to Christ's intent in coming to die, i.e. it was for his elect ones. Some Calvinists think that intent was

exclusively for the elect alone (the

strictly limited view), while others sees additional motives concerning all of lost humanity (the moderate view). The expression "limited atonement" should not merely be associated with the strict view. Even the moderate Calvininsts, like myself, Charles Hodge, R. L. Dabney and Shedd, maintain that there is a special design/purpose/intent in Christ's coming to die in the case of the elect. Some push the limitation idea into the very nature (not merely the intent) of Christ's death by

commercial or pecuniary debt payment notions, i.e. he

literally purchases things for the elect alone. Moderate Calvinists say the limitation is only in the special decree to effectually apply the death (which death, intrinsically considered, is unlimited in terms of it's legal accomplishment - he suffers or bears the full curse of all that the law requires of any given sinner) to the elect alone by the Spirit through the instrumentality of faith.

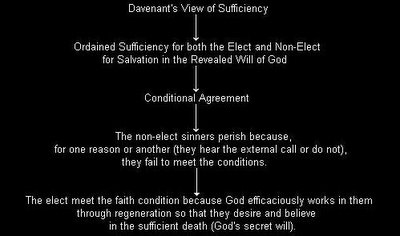

The positions on the intent issue are not merely between 1) an exclusive or singular intent to come and die for the elect alone (the strictly limited view) and 2) a singular and equal intent (same motive for every lost person) to die for every one (Arminianism); but there is, at least, a third view: 3) Christ came to die for all (general motive), but especially for the elect (special motive). This third view is related to the issue of God's love. He loves all mankind, but especially his elect (his bride). It's a false dilemma to posit either that God only loves the elect or he loves all equally, just as it is a false dilemma to posit that either Christ died only for the elect, or he died with an equal intent for all. I assume that you are not positing these dilemmas, but I am just addressing this issue in case you see it elsewhere.

2) With regard to the issue of propitiation, Christ certainly came to satisfy God's wrath against sinners. However, as the scriptures say, we come to be at peace with God at the point of conversion or faith. Prior to that, we are children of wrath, even as the rest, as Paul says in his letter to the Ephesians. So then, God was propitiated in the case of Laura when she believed. Prior to that, Christ was the provisional means by which God could be propitiated towards Laura, but you abided under his wrath until the point of faith, or real union with Christ. Propitiation is scripturally associated with forgiveness of sins, restored peaceful relations, and justification. If we push the doctrines about what occurs at the point of real union (our actual union through faith) with Christ back into the point of our federal union (our decretal union with Christ prior to our existence), then we virtually arrive at our justification at the time of the cross, or in eternity (two versions of theoretical antinomianism). This undermines our responsibility to believe in order to be justified (what some in the past called "duty-faith"), as well as the doctrine that elect sinners are under God's wrath prior to faith.

Even though Christ died especially for Laura as an elect sinner, the benefits of what he did in her case were suspended until she performed the decreed condition for the reception of his merits, namely faith or trust in Christ alone (which Laura was only able to perform because the Holy Spirit, through regenerating power in her heart, granted her the moral ability to do so - contra Arminianism). Had Laura not performed this necessary condition, then she would have remained under God's wrath.

3) You ask, "If Christ died for all sinners, the fact that the non-elect are called "vessels of wrath" (Rom. 9) who are storing up God's wrath in their present rebellion seems to mean that Christ's death did not satisfy God's wrath for those who are bound for eternal punishment. How could we still say, then, that Christ died for the sins of "the world" in the sense of "every individual" and not "elect from all nations?"

The reason why Christ's death does not atone for these "vessels of wrath" is because they remain in unbelief. They fail, for one reason or another, to appropriate the remedy. They do not look to the lifted up serpent with the eyes of faith to heal the bite of sin (John 3:14-17). Christ satisfies for all that the law requires, but it does not avail anyone who remains in unbelief, therefore

Calvin says, "And the first thing to be attended to is, that so long as we are without Christ and separated from him, nothing which he suffered and did for the salvation of the human race is of the least benefit to us." In Calvin's way of putting it, Christ can die for the sins of the "human race" or "the world", but it does not follow that they are

ipso facto liberated. One must be really united to him (i.e. not "seperated" or "without Christ" as Calvin expresses it) through faith to receive the benefits.

4) Incidently, nowhere in scripture does "world" or kosmos mean "the elect from all nations." The "world", biblically, refers to sinful and darkened humanity in organized hostility to God, or to the sphere or location in which these sinners dwell. Even when the "world" in scripture means the location of sinners ("Christ came into the world" etc.), it still carries the association with the first sense, i.e. to sinful humanity. "World" has morally dark connotations. It's put in contrast to the "light."

Those inclined to see "world" as meaning the "elect from all nations" are taking high Calvinist interpretations. The people who usually take this view are picking it up from recent "Calvinistic" (actually not from Calvin) literature steeped in Owenic and Post-Reformational scholastic categories (like G. Clark, Sproul, White, etc). Some even get it from Arthur Pink, one who was, at least when he wrote his book

The Sovereignty of God, influenced by John Gill (a hyper-Calvinist who denied free offers and duty-faith [

Pink accepted "duty-faith"]).

What I am saying is that taking the "world" as entailing "the elect" is a high (although not necessarily hyper) Calvinist path. One does not have to take that method of interpretation to remain a solid, historic Calvinist in harmony with the Synod of Dort. The Calvinists who say that there is a sense in which Christ died for the whole world are not necessarily "4 point" Calvinists. They may be 6 point Calvinists. They wish to add a point of clarification, namely that Christ really or actually suffered sufficiently for all mankind (it's no mere hypothetical sufficiency "had God so intended", contra Owen), in addition to the teaching or truth that he died especially for the elect (contra Arminianism).

5) I've been meaning to post a blog on the issue of either "all without exception" vs. "all without distinction" for awile now, but have not done so yet. This issue is related to the "world" interpretation you mention above. There are logical leaps that ofter go undetected. I will try to address this issue as soon as possible, because it is related to high Calvinistic hermeneutics.

It's hard to find Calvinistic critiques of high Calvinistic interpretive methods and theology. In some ways, my blog is a collection of some of my efforts to deconstruct their thinking patterns, and analyze them biblically and systematically (I am a different kind of Calvinistic Gadfly). We are attempting do this same thing at the

Calvin and Calvinism list, as you know. We have addressed the "all without exception" vs. "all without distinction" topic there, but I need to post something on my blog about it. I will do so asap, because it is related to the "world" means "elect" subject.

I hope that all of the above helps to clarify your thinking on the issues, even if you end up disagreeing. These subjects are worthy of constant and serious contemplation/meditation. I also hope that things I have said in this post encourage you to reflect and think critically about your own theological presuppositions. Becoming epistemologically self-aware, as you know, is an aspect of becoming intellectually virtuous :-)

In him,

Tony

Other Helpful and Related Posts: